I want to highlight an issue that is currently being debated as part of our thinking about conservation and agriculture. Some conservationists are pointing out that the UK’s traditional focus on sheep farming could be reconsidered.

Sheep grazing on rolling green fields is a quintessential image of English country life, but perhaps there could be a different approach. It’s a topic of particular interest to me because of our environmental project at Ewhurst Park, Hampshire, where we are turning a former pheasant hunting estate back to nature.

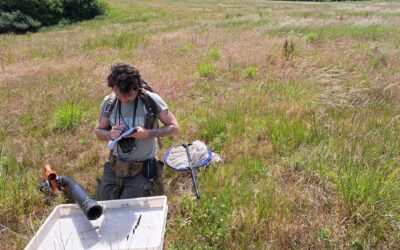

Our focus is on regenerating the land while operating a working farm that employs environmentally-friendly techniques, one of which is to keep free-roaming livestock. We currently have Longhorn cattle, Iron Age pigs and a few mouflon sheep. In our efforts to establish chalk grasslands, I’ve learned that sheep are one of the best management tools due to the way they graze. While talking to farmers and experts, I have learned that a high stock-density of grazing sheep can deplete the soil on certain types of land.

Is it time to rethink our traditional focus on sheep farming?

Over the centuries, sheep farming has gradually expanded such that huge swathes of wood pasture and temperate rainforest have been given over for grazing. In the modern era, an additional issue is that the chemicals used to treat the parasites on sheep have been seeping into the land and water table. Furthermore, sheep strip away plant life, so the land struggles to retain water, leading to soil erosion.

A second point is that it seems a sheep’s life is not necessarily a happy one. Biologically, it seems sheep are better suited to the arid hills of Asia Minor, where they originated before being introduced into the UK by neolithic settlers and the Romans. Having never really adapted to the UK climate, many sheep suffer from severe foot rot due to the rain-sodden land.

A third point is an economic one. Historically, some commentators have observed that EU farming subsidies encouraged sheep farmers to operate at a financial loss. Under such schemes, farmers found that the more sheep they acquired – meaning turning over more land for grazing – the more profit they made. The UK is now creating fresh policies – such as The Agriculture Act (England) 2020 – which should address this issue by offering financial incentives to farmers to care for the land.

As mentioned, no-one is saying ‘no sheep’. We have some mouflon sheep at Ewhurst Park. There are types of landscape, such flower-rich hay meadows, that benefit from grazing sheep, especially when this is part of a rotational farming practice. And, interestingly, it has been found that sheep are suited to grazing on solar farms because, unlike cows, there isn’t a risk of sheep knocking into equipment and damaging it.

It is possible to help sheep farmers diversify towards new forms of income. Indeed, many would welcome it: the average age of sheep farmers is increasing, and their average income decreasing, which seems to show it is a type of farming fraught with difficulty.

And a note on wool: it seems this is not a key factor in the discussion. According to gov.uk: ‘Few sheep farmers are now reliant on their wool cheque, with income from wool making up less than 3% of sheep revenue in 2019, and an even lower proportion of [sheep farmers’] overall income.’

It must be acknowledged that sheep farming is a part of the conversation about our care for the environment. I can’t claim to have all the answers; rather, my wish is to encourage debate so the facts can come to light and be considered. The key point is we need to radically rethink our relationship with nature and rethink how we live. There has to be space for both nature restoration and farming.